William Hogarth

William Hogarth was the outstanding figure in artistic life in early Georgian England, the first British painter to achieve international fame. Hogarth was instrumental in establishing both an autonomous identity for British art and a space for its exhibition; he invented an entirely new and democratic art form and had a copyright bill named after him. A fascinating personality, rich in intriguing contradictions and with a boundless imagination, Hogarth made his mark indelibly on the period and on the place he lived; his art was shaped by both of these and illuminates both in intimate detail.

Hogarth lived and worked all his life in London. His art was intrinsically involved with the city as the hyperactive focal point of an increasingly commercialised imperial nation, in which royal and religious influence were replaced by what was in effect the beginning of the modern consumer society. The demand for art came increasingly from the new middle classes, wealthy from trade and industry. Artistic taste was dominated by the work of Continental painters, and until the early 1700s there was no distinctive "British" school of painting. Hogarth, who had his own powerful moral and artistic integrity, balanced his career finely between the financial need to accommodate the taste of this new class of patrons, his desire to provide a critique of the downside of fashionable London life and his striving to be taken seriously as a British artist.

The precarious circumstances of Hogarth's early life helped to define his artistic personality and his subject matter, and explain his extraordinary drive and ambition. Hogarth was born in 1697 near Smithfield Market, London. He experienced poverty early, spending his later childhood with his family in Fleet debtors' prison after his father's failure to make a living from teaching, writing and running a coffee-house. Hogarth's apprenticeship to a silver engraver was to provide him with a financially sound career based on his evident drawing ability. Despite his impatience with the "Narrowness of this business", Hogarth established his own engraving workshop in 1720, developing his own graphic style in original satirical engravings and carrying out more humdrum commissions for trade cards and book illustrations.

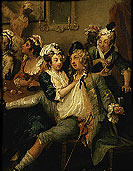

At the same time Hogarth enrolled in the new art academy in St. Martin's Lane. There he met other aspiring and well-known painters, including Sir James Thornhill, the first British painter to compete seriously with the Continental painters working in London. Hogarth later attended Thornhill's own art academy in Covent Garden, and secretly married his daughter Jane in 1729. Hogarth always described himself as self-taught, and, although he went to the academies' life drawing classes, developed his own highly personal way of training his extraordinary visual memory by direct observation of life around him rather than copying old masters or taking lessons from other painters. Hogarth made astonishingly rapid progress; his first successful work was an innovative depiction of a performance of the popular satirical play The Beggars' Opera, by John Gay. Hogarth's interest in the theatre was a crucial part of his life and art; one of his lifelong friends was the actor John Garrick. Hogarth was keen for commercial success and public acclaim, and in the late 1720s established himself as the major painter of fashionable "Conversations". These were small-scale group portraits of the aristocracy or newly-arrived bourgeoisie, involving the sitters in elegant social interaction, influenced by the delicate style of French Rococo painters like Watteau. Hogarth communicated the vitality and immediacy of theatrical performance in these portraits, often adding visual humour to the scene, providing a liveliness and effervescence which transcends the potential formality of the standard group portrait. He wrote: "Subjects I consider'd as writers do; my Picture was my Stage and men and women my actors." Hogarth was a shrewd and practical businessman, as well as artistically ambitious, and despite the reputation and social status that these pictures brought him, felt that the "Conversation" portrait fees did not provide him with sufficient income. In his own words, "I therefore recommend[ed] those who come to me for them to other painters and turn[ed] my thoughts to still a new way of proceeding, viz. Painting and Engraving modern moral Subject[s] a Field unbroke up in any country or any age." These series of "modern moral subjects", or "Progresses", beginning with the six part Harlot's Progress, in 1731, constituted a completely new art form that became Hogarth's best-known legacy. The paintings made a satirical narrative that used recognizable London characters and places to describe the fate of young people corrupted by the shallowness and ruthless hypocrisy of contemporary London life. The series combined Hogarth's skill as a painter with his interest in satirical theatre and literature. The writer Charles Lamb commented later, "his graphic representations are indeed books: they have the teeming, fruitful suggestive meaning of words. Other pictures we look at - his prints we read."

The Harlot's Progress was an enormous success, and suited Hogarth's needs - he reportedly able to sell by subscription at least 1240 sets of engravings from the paintings, thus enlarging the audience for his work and freeing him from dependence on the patronage of the aristocracy. The rampant pirating of cheap prints of the series ("destructive to the Ingenious", as Hogarth remarked, remembering his father's exploitation by unscrupulous printers) made him the moving spirit behind the Engravers' Copyright Act, passed in Parliament in 1735. Hogarth published engravings of his later series, The Rake's Progress, the day after the act became law, and in 1743 he produced Marriage a la Mode. These were both witty commentaries on the triviality and moral vacuousness of fashionable high society life in London, the visual equivalent of his close friend Henry Fielding's satirical novels. Later, Hogarth made his unequivocal moral message accessible to all corners of society in series produced as cheap popular engravings, like Industry and Idleness (1747), which extolled the merits of hard work and industriousness. Hogarth's moral approach and concern for vulnerable young people in Georgian London was reflected in his involvement in contemporary philanthropic initiatives. Hogarth was a governor of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, for which he had painted The Pool of Bethesda and The Good Samaritan in 1736-7 without a fee (albeit to wrench the commission from a rival Italian painter, Amiconi). For Captain Thomas Coram's. Foundling Hospital for orphans, established in 1740, Hogarth not only contributed paintings for the grand public rooms, but also persuaded other eminent British painters to donate works to hang in the Hospital, thereby creating the first public collection of British painting.The importance of this British context for art was crucial to Hogarth. He was fiercely patriotic, proud to belong to the new Great Britain (England and Scotland were united politically in 1707) and pugnaciously nationalistic about the importance of British-born painters; he signed himself on occasion "Britophil". In his satirical series he remorselessly denigrated fashionable London's preference for Continental art, and refused to acknowledge the authority of the old (European) masters. Hogarth's almost propogandist engraving Beer Street presents a scene of urban prosperity and contentment, apparently the result of the consumption of British produce and goods, and in particular British beer. Hogarth's pro-British agenda, implicitly attacking the "Frenchification" of British taste and fashion, is seen at its most overt and venomous in his xenophobic The Roast Beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais) of 1748-9. Hogarth's famous 1745 self-portrait The Painter and his Pug includes a pile of books by Milton, Shakespeare and Swift, indicating his allegiance to English literature. Hogarth's later portraits of individuals are among the most interesting of the Georgian period. His celebrated 1740 portrait of Captain Thomas Coram, a successful shipbuilder, was groundbreaking in being a grandiose representation of a man of commerce (rather than an aristocrat), and showed Hogarth's technical brilliance in bringing informality, truthfulness of characterisation and vitality to the conventional format. His Heads of Six of Hogarth's Servants, painted in the early 1750s, shows amazing spontaneity, painterly expressiveness and respect for the individuality of the sitters.

Hogarth was strongly anti-academic in his approach to artistic practice. In 1753 he expressed his views in his book The Analysis of Beauty ("written with a view to fixing the fluctuating ideas of taste"), in which he used a serpentine line (his famous "line of beauty") to illustrate the fact that aesthetic beauty derived from real, observed visual experiences in life. His own art academy, which he inherited from his father-in-law, Thornhill, maintained a free, idiosyncratic creative atmosphere. However, Hogarth was seen increasingly as unorthodox and out of kilter with mainstream British art practice. He objected to the founding of a formal national academy of art, fearing that it would be based on the rigidly hierarchical French academies and pander to the connoisseurs' taste for Continental art, and quarrelled publicly with Sir Joshua Reynolds, who in 1768 (four years after Hogarth's death) became the first president of the new Royal Academy of Arts.Hogarth's last years were dogged by these disputes and squabbles, as well as hostility from the academically-minded cultural elite in London who thought of Hogarth merely as a satirist and accomplished portraitist, and not capable of excellence in the accepted highest form of art, history painting. Hogarth's last attempt at this kind of work, Sigismunda mourning over the heart of Guiscardo, was refused by Sir Richard Grosvenor who had commissioned it in 1759, and generally considered an artistic catastrophe. Hogarth's appointment in 1757 as "Serjeant Painter to the Monarch" (George II and III) compromised his position as a political satirist, and his artistic credibility suffered damaging attacks in print. He died in his house in Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square) in 1764, survived by his wife Jane, and was buried near his country retreat in Chiswick.

Hogarth's versatility and inventiveness ensure his central position in the history of British art; his status as one of the greatest of eighteenth-century painters, however, is fairly recent. For two centuries after Hogarth's death, he was mainly appreciated as a graphic satirist and chronicler and interpreter of life in Georgian London. The literary aspects of Hogarth's work were seen as the most important: Charles Dickens drew on Hogarth's work in the nineteenth century, and the writer William Hazlitt remarked that as a comic author he was second only to Shakespeare. In the later eighteenth century, the graphic wit of the political caricaturist James Gillray and the social satirist Thomas Rowlandson owed much to Hogarth's example. The Victorian age identified with Hogarth's patriotism and anti-aristocratic stance, and their painters of urban life referred to Hogarth in their crowded and incident-filled canvases. David Hockney produced a series of prints for his own Rake's Progress in the 1960s, and the satirical work of twenty-first century cartoonists such as Steve Bell and Posy Simmonds bring a Hogarthian aspect to our own time.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home