Workshop of the world

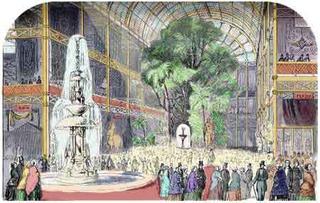

When Queen Victoria opened the Great Exhibition on 1st May 1851, her country was the world's leading industrial power, producing more than half its iron, coal and cotton cloth. The Crystal Palace itself was a triumph of pre-fabricated mass production in iron and glass. Its contents were intended to celebrate material progress and peaceful international competition. They ranged from massive steam hammers and locomotives to the exquisite artistry of the handicraft trades - not to mention a host of ingenious gadgets and ornaments of domestic clutter. All the world displayed its wares, but the majority were British.

All the world displayed its wares, but the majority were British.

This dominance was both novel and brief. It was only half a century earlier that Britain had wrested European economic and political leadership from France, at a time when Europe itself lagged far behind Asia in manufacturing output. By 1901, however, the world's industrial powerhouse was the USA, and Germany was challenging Britain for second place. But no country, even then, was as specialised as Britain in manufacturing: in 1901 under ten per cent of its labour force worked in agriculture and over 75 per cent of its wheat was imported (mostly from the USA and Russia). Food and industrial raw materials, sourced from around the globe, were paid for by exports of manufactures and, increasingly, services such as shipping, insurance and banking and income from overseas investment. Nor was any other country so urbanised: already in 1851 half the population inhabited a town or city; by 1901 three-quarters did so. Yet even in 1851 only a minority of workers was employed in 'modern' industry (engineering, chemicals and factory-based textiles). They were largely concentrated into a few regions in the English north and Midlands, South Wales and the central belt of Scotland - where industrialisation was evident by 1800.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home